Schools and Colleges

Watch Philip Esler, Portland Professor in New Testament Studies in the University of Gloucestershire, discuss how the project came together and see if you have what it takes to create a response to 1 Enoch

What we want you to do

Be Inspired.

Students and staff are invited to experience the amazing exhibition virtually and record your responses to the artwork and text.

Create a response to the project.

Use any medium to create a response to the exhibition, such as painting, collage, sculpture, photography; or even by writing a short essay of no more than 250 words or by filming a Vlog (5 mins maximum).

Have your work hung alongside 1 Enoch’s.

Selected entries will be chosen by academics who will print and display entries, along with the students’ names and schools and these will be displayed in Gloucester & Canterbury Cathedrals*. In addition, they will also be available to view them via the University of Gloucestershire’s website.

*It is the intention that entries will be displayed in public venues such as cathedrals, however this is subject to change based on government guidelines for Covid-19.

Your responses to the exhibition must be submitted by

5pm on Monday 31st August

Successful entrants will be contacted by email no later than 28th September. Entries can be submitted via email to:

We value your feedback

Thank you for your participation in this exhibition. Please complete our short evaluation to let us know about your experience. It should take around five minutes:

Any information collected will be used solely for evaluation purposes, including in relation to the evaluation of impact in the UK-wide Research Excellence Framework. You are welcome to email the outreach team directly outreach@glos.ac.uk if you have any questions or comments.

Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger

An exhibition of twelve paintings on 1 Enoch and an illuminated model of an Ethiopian church by Angus Pryor

Angus Pryor

An Intro to 1 Enoch

Philip Esler

How the project came together

“Wherever we went in the country, we were overwhelmed by the religious faith of the Ethiopians, and by their remarkable art and architecture”

Take a virtual tour

Explore the exhibition in person, through an amazing 3D walkthrough

Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger

Overview

1 Enoch is a work written in stages by Jewish scribes in Israel from about 300 BC to 100 AD. It is an apocalyptic text, meaning it contains revelations by a heavenly figure to a human being or beings concerning the nature of the cosmos and the secrets of God’s divine purpose for humanity, and for creation and its renewal. In this case the heavenly figure is Enoch, who, when he was 365 years old and not long before the Flood, was taken to heaven still alive (Genesis 5:24). A group of Jewish scribes, believing Enoch still to be in heaven, portrayed him as a scribe (like them). They then used him as their mouthpiece to write about the problem of evil and its ultimate resolution, the state of life on earth and issues of justice and peace.

The primary narrative in Chapters 1-36 is of the Watchers, angels who abandoned heaven to marry human wives and to reveal heavenly secrets about things like weapons, spells and magic, female decoration and the mysteries of the heavens. But their marriages led to the birth of Giants who ravaged the earth, while their revelations contributed to an explosion of evil, so God sent the Flood. At one point, Enoch wrote a petition to God on their behalf, but to no avail. The Watchers were bound in hollows in the earth until the End-Time. The Giants were killed. After these events, Enoch is taken on a tour of the cosmos by various angels and writes up all that he sees. Eventually, in Chapter 71, Enoch is transformed into the Son of Man.

The Individual Paintings

God and the End-Time Punishment

(1 Enoch 1:4-9)

1 Enoch begins with a statement of how it will end: God will visit the earth with his army of angels, tearing the earth asunder, executing judgment on the wicked and making peace with and blessing the righteous. The long battle against evil will finally be won. In a painting in which the heavenly realm is depicted in gold and thus sharply differentiated from the earth that is painted in red and black, God appears with his army of angels. He and they are represented in an Ethiopian pictorial style. Details of the painting in the lower half of the canvas refer to the fate of the wicked.

The Descent of the Watchers

(1 Enoch 6:1-7:1)

A key narrative in 1 Enoch concerns how a group of the angels who serve as sentinels, ‘Watchers’, in heaven descend to earth to take human wives. In so doing they rebel against God, by abandoning their appointed post as courtiers in God’s heavenly court. Their human wives later give birth to Giants who ravage the earth. In the painting we observe one Watcher descending to the woman he has chosen, his hand reaching lustfully out towards her. White flowers symbolising her innocence are contrasted with red lines suggesting the potency of the Watcher and fate in which he will ensnare her. The two figures are painted using body prints of actual people.

Asael Teaching Metalwork

(1 Enoch 8:1)

One of the leaders of the Watchers is called Asael. On earth, in breach of divine command, he taught men how to make swords of iron and every type of implement of war and also how to fashion gold and silver into jewellery for ornaments for women. He also taught women the uses of cosmetics and precious stones. In the painting Asael is depicted as he is about to reveal these secrets. This is a version of the Prometheus myth. Much evil and desolation resulted on earth from Asael’s revelations, as represented by black crows, spiders and bats crawling across the canvas as they invade God’s sacred cosmos. The notion of metalwork, the primary focus of Asael’s revelations, is portrayed by the heraldic shields with swords. The three faces at the bottom of the canvas are women being told about cosmetics as they look up at Asael.

The Earth Cries Out

(1 Enoch 7:6)

The Giants that resulted from the union of Watchers and women devoured human food and then began devouring human beings themselves, before turning on animals, birds and fish and even one another. As a result, the earth cried out (i.e. to God in heaven) against them. The painting depicts Enoch’s vision of the fate of the earth, using three globes to represent three phases in the earth’s ecological history, with the oldest, in Prussian blue symbolical of the Flood, in the background. The second earth, with a green land mass and blue sea, could be contemporary, still beautiful but with poison mushrooms of human misuse spreading across its surface. The third, golden earth has Ethiopia as its focus. Calla Lilies (Ethiopia’s national flower) grow out to form a mouth from which the earth’s agonised scream emerges. Yet there is hope in the antlers that burst through the surface, reaching out to the heavens for help.

God on His Throne

(1 Enoch 14:18-21)

Once translated to heaven, Enoch came to an antechamber beyond which he saw God on his throne. The throne was round like the sun, and it's appearance a paradoxical mixture of ice and fire. God himself was as bright as the sun and neither angel nor human being could enter the throne-room to look upon him. The flat, two-dimensional mode of representation and the portrayal of God’s face are recognizably Ethiopian. The colours of the rays round God pick up the ice and fire of the text but are also used in Ethiopian paintings of the Holy Trinity. The two modified deer-heads refer to the mysterious creature of 1 Enoch 90:38, the Nagar, who symbolizes Enoch’s revelations throughout the series. The painting exemplifies the artist’s post-conceptual approach to artistic making that includes adding ready-made objects to the canvas, such as dolls, fruit and birds. Ultimately, the painting asks, ‘What is God?’

Enoch Writes the Watchers’ Petition by the Waters of Dan

(1 Enoch 13:4-7)

After the descent of the Watchers to earth and the devastation that ensued, the angels in heaven sent Enoch to them with the message that they would not be forgiven. So the Watchers asked Enoch to write a petition to God on their behalf, begging God to reconsider. Enoch agreed, thus exemplifying his function as a scribe, an important theme in 1 Enoch, since he was the eponymous hero of a group of Israelite scribes. As a scribe, he became the alleged source of their own writings on the righteous and the unrighteous, and on the nature, history and ultimate destiny of both humanity and the cosmos itself. The painting shows him sitting by the waters of Dan writing the petition, the words on it being the text of 1 Enoch 13:6 in Ethiopic (or Ge‘ez). In the painting Enoch has been represented in characteristic Ethiopian pictorial style. Enoch’s face radiates compassion.

The Imprisoned Angels

(1 Enoch 10)

The earth’s cry of distress was heard in heaven and God sent angels to punish the Watchers, about the time of the Flood. Raphael bound Asael and cast him into darkness in the wilderness of Dudael, putting sharp rocks over him until the final judgment, when he would be led away to the burning conflagration. The other Watchers were punished in similar ways. The painting shows Asael beginning to sink into the rough and jagged rocks of Dudael. He still has his angel’s wings but his facial expression shows that he has lost God as his saviour and has forfeited his angelic rights. Pain and suffering are apparent in the red rocks that symbolise earth and the destruction of humanity, because Asael taught them secrets from heaven. The Nagars, Enoch figures, and the Ethiopian cross bear witness, so that all generations will know what happened here.

Abel’s Cry for Vengeance on Cain

(1 Enoch 22:5-7)

Cain murdered his brother Abel because God preferred Abel’s offering of a sheep to his grain (Gen. 4.2-8). For the Enochic scribes this act of homicidal violence was the first and most troubling human sin, not the actions of Adam and Eve. At one point during his tour of the cosmos Enoch comes to a mountain with hollow places containing souls of the dead until the End-Time. In one of these Abel makes accusation against Cain. The artist has sought to capture the moment just before the fatal attack in order to examine the intent to kill. A sharp, jagged flint lies in wait on Cain’s side of the painting. Stretching across the painting is a sheep carcass: this is the offering Abel that gave to God. The two yellow suns at the top and bottom of the painting represent life and death. The orange sun signifies God’s disappointment and the transition of Cain to sinfulness and mortality. The painting is asking what will be the consequences of this initiation of violence for humankind?

The Tree for the Righteous at the End-Time

(1 Enoch 24-25)

At another point on his journey Enoch comes to a mountain on which is a sweet-smelling tree, which will be transferred to Jerusalem in the End-Time. On this mountain God will sit when he descends to earth to punish the wicked and reward the just. The painting depicts God at the moment of his descent, when he is directly above the tree. In a sense God has become the tree. God is painted in Ethiopian style and colours. The two birds with spotted wings, which evoke some of the Ethiopian birds depicted in the ancient Garima Gospels (preserved in the Garima monastery in Ethiopia), act as (good) Watchers, guarding the deity. The painting is grounded by the (flat) earth, with the Tree for the Righteous springing up like an eternal fountain. Mushrooms and insects gather around the bottom of the tree to represent a pilgrimage of mankind to the Tree after the last judgment. The Nagar reappears as a sign of Enochic revelation. The painting celebrates the Tree for the Righteous.

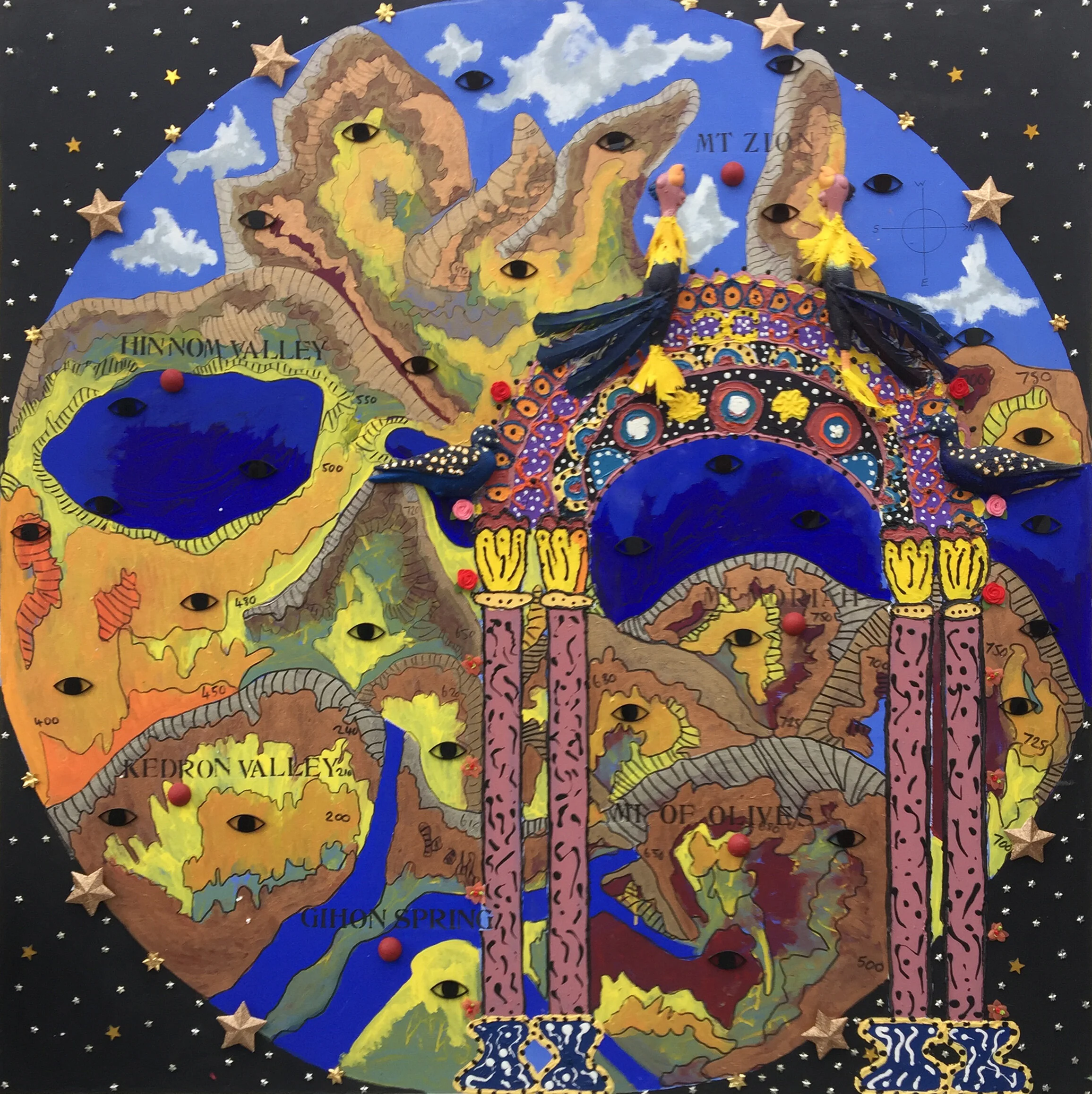

The Topography of Jerusalem

(1 Enoch 26-27)

Enoch is also taken to a place, described as the centre of the earth, where Jerusalem will later be built. He describes the mountains, valleys and streams of a topography that is recognizably Jerusalem, yet with no buildings. The artist has based his painting on a contour map of the location. But the painting also points to the site’s future, since the potency of the place cannot be constrained within a mythological past. Its tumultuous future seeps out from the bare earth, from those precious valleys and hills, and expresses itself in various ways on the canvas. Hence the identification of topographic features with the names that they would only acquire long after Enoch’s visit. The arch, which acts as an entrance to the painting, has a similar function. It is modeled on an image of the temple in Jerusalem in one of the Garima Gospel Books. Finally, the eyes in the painting are Ethiopian eyes looking directly at the audiences. They are watching the proceedings going forward, from the mythical realized past and beyond. Here Ethiopian tradition acts as the gateway to Heaven.

Enoch’s Journeying to the Ends of the Earth

(1 Enoch 33-36)

This painting focalizes Enoch as learned in cosmography, especially astronomy, an area of knowledge that formed the original interest of the Enochic scribes. Enoch observes the three gates that exist on each of the four sides of heaven— north, west, south and east. Through these gates the sun, moon, planets and stars rise and set and from them come the winds. The artist has sought to illustrate how God and the angels gave Enoch the opportunity to survey the celestial universe because of his elevation to heaven while still alive. We see Enoch in the presence of his guide, the archangel Uriel. Enoch has a golden hue and wears a wooden orthodox Ethiopian cross symbolising his pure yet earthly status. Not all that Enoch witnesses is beautiful; some of the scenes fill him with dread. The portals, represented by mirrors, are symbols of the gateways into other parts of the celestial universe. This is a self-reflecting and contemplative painting, charged with endless potential for one’s self.

Enoch’s Transformation Before the Angels and God

(1 Enoch 71:11)

In 1 Enoch 37-71, ‘the Book of Parables’, a figure called the Son of Man makes his appearance, as a staff to the righteous and as someone chosen and hidden in God’s presence before the creation of the world (48:4, 6; 62:7). Quite remarkably, Enoch is identified with this Son of Man (71:14). In Ethiopia, the Enoch-Son of Man figure was further identified with Jesus Christ. In the painting Enoch’s reconfiguration as the Son of Man is represented by his being visualised twice: as a human being and then (above and to the right) as the Son of Man. In the first phase Enoch kneels on a bed of flowers to show that he is in touch with the earth, an earth that earlier in the text cries out at the indignities that are being visited upon it. In the next phase Enoch begins to enter the flames that surround God. Umbrellas are regularly used in Ethiopian Orthodox ceremonies and the two umbrellas in this painting celebrate Enoch’s ascension and God’s oversight of the process. The painting proclaims that humanity can be saved and that God will transform the righteous.

Explore a 3D walkthrough of the Book of Enoch

View the collection of Pryor’s Book of Enoch work