The Topography of Jerusalem

(1 Enoch 26-27)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

The first part of 1 Enoch 1-36 consists of the action set in heaven and on earth involving the Watchers and Enoch’s role in relation to them at God’s command (1 Enoch 1-16).74 The second half of 1 Enoch 1-36 describes journeys undertaken by Enoch across the cosmos in the company of angelic guides. The first of the two journeys, to the north-west, occupies 1 Enoch 17-19.75 His second journey, comprising 1 Enoch 20-36, is to the east. During the course of this journey he reaches a destination that is recognisable from the way that its topography is described (1 Enoch 26-27). It is the site of Jerusalem, although before the construction of the city, and it is a place described as being the centre of the earth:

- And from there I proceeded to the center of the earth, and I saw a blessed place where there were trees that had branches that abide and sprout.

- And there I saw a holy mountain. From beneath the mountain water (came) from the east, and it flowed toward the south.

- And I saw to the east another mountain higher than it, and between them a deep valley that had no breadth, and through it water was flowing beneath the mountain.

- And to the west of this, another mountain lower than it and not rising very high, and a deep and dry valley beneath it, between them, and another deep and dry valley, at the apex of the three mountains.

- And all the valleys were deep, of hard rock, and no tree was planted on them.

- And I marveled at the mountain, and I marveled at the valley, I marveled exceedingly (26:1-5).

Commentators have noted how the passage represents a close and detailed description of the topography of Jerusalem and its immediate environs.76 Thus the ‘holy mountain’ (v. 2) is Mount Zion (Moriah, the hill on which the Temple would be erected, although the Temple is not mentioned here). The water coming from the east (v. 2) is Gihon, flowing at first towards the south, and thence out into the Kedron Valley. To the east of Zion is a higher mountain (v. 3), the Mount of Olives. The deep valley between them is the Kedron Valley (v. 3). Finally, the last mentioned ‘deep and dry valley,’ at the apex of the three mountains (v. 4), is the valley of Hinnom (= Gehenna), which is probably to be identified with the valley mentioned in 1 Enoch 27 as the ultimate gathering place for those who are cursed forever. The certain identification of other features is rendered difficult because of textual variations.

It was common in the ancient world for ethnic groups to regard their land, especially its principal cultic site, as the center of the earth, a view often associated with the notion that ‘our world’ is ‘the world’.77 Delphi, for example, featured a large stone omphalos, a ‘belly-button’, as a means of manifesting this claim by the Greeks in a physical way. A version survives and is kept in the museum there. Here we see an example of this among Israelites. In Ezek 5:5 God declares, ‘This is Jerusalem; I have set her in the center of the nations; with countries round about her.’ The author could be borrowing from Ezekiel (here and in 38:12), as VanderKam suggests.78 Alternatively, he could just be giving expression to a belief that Jerusalem was the centre of the earth, which Richard Bauckham has shown was commonly held among Israelites.79

In 1 Enoch 26-27 none of these features of the topography is named, nor in this section of the text is there any mention of the city that would be built there or the Temple it would have at its heart. The author leaps over these developments that lay in the future beyond Enoch, and moves to certain features of the ultimate future,80 when the cursed will dwell in the valley of Hinnom forever, somehow in the presence of the righteous (1 Enoch 27). Since 1 Enoch 25:5 probably entails that the Tree of Life will be transported to a site next to the Temple in Jerusalem in the End-Time, the likely result is that the righteous will be entering the sanctuary and enjoying its fragrance while, not far away, the cursed are gathered forever in Gehenna. As a result, while 1 Enoch 25:5 requires us to assume the existence of the Temple in the time up to the end, the author of 1 Enoch 1-36 evinces no interest in its role during that period. That is why he can describe the topography of Jerusalem in 1 Enoch 26-27 without mentioning it. In Israelite history and tradition, Jerusalem would eventually become the mother-city (mêtropolis in Greek) of the Israelites, the capital of the homeland, so often a feature of ethnic identity. This applied a fortiori for Israelites who had only one God whose cult was observed in the Temple in Jerusalem. Yet here the author is in no way concerned with the function of the land, its capital with its cultic centre as contributing to the ethnic identity of the Israelites. True, the eschatological Temple will see service during the ultimate future beyond the great judgment; yet what happens until then (including the role of the historical Temple) is largely immaterial. For these reasons it is submitted that this section of the text is appropriately called ‘proto-ethnic.’

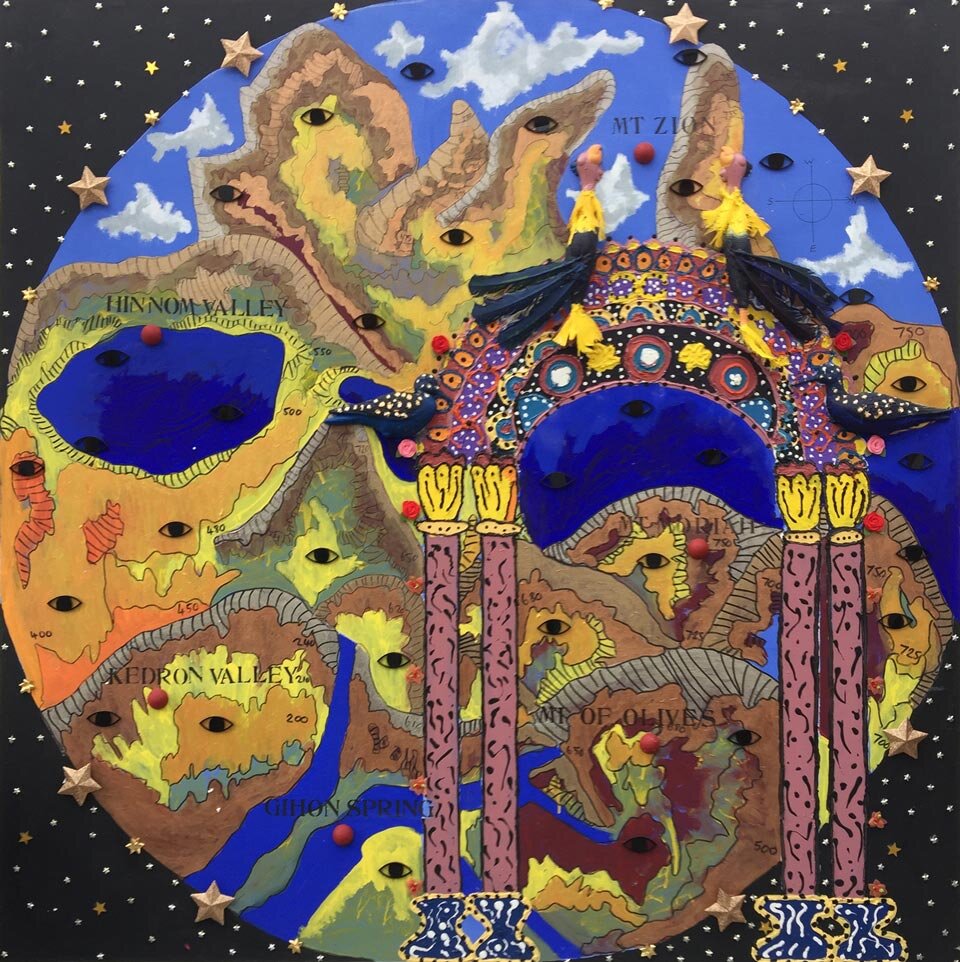

In the painting The Topography of Jerusalem (1 Enoch 26-27) the artist has created the painting as a vision. He has sought to express features of the text but also to introduce some recognition of what would happen in this place in the future beyond Enoch’s description of it. For the artist, the potency of the place proves impossible to constrain within a mythological past; its tumultuous future seeps out from the bare earth, from those precious valleys and the hills, and expresses itself in various ways on the canvas. The use of words to identify topographic features with the names that they would only acquire long after Enoch’s visit is one sign of this. So too is the arch (see below).

Since this place, the site of Jerusalem, is described as the centre of the earth in the text, the artist has created the composition in such a way that it can be seen or drawn in three ways. Firstly, it is isolated and floating as if in a bubble in the celestial atmosphere; it is tentative and inchoate, a ‘creating’ that has been made but not finalized and awaits its time of use. It is partly structured topographical material for a great world-building enterprise. Many of the elements in the painting are mythical. Secondly, however, the essence of the painting is the symbiotic relationship between the artist’s conception, Enoch’s aerial view of the topography and these mythical dimensions. In other words, while the text creates a space that is appropriately designated ‘proto-ethnic,’ the painting accepts that space but also imagines it as a space that will happen. So space is re-imagined as plan. The painting is a laid-out space being prepared for a future moment which has a sense of what will happen to its own self.

Thirdly, it is like having a spot-light on one element (the ethnic Israel that is to come) so that it can be highlighted. The painting floats between mythical and instructional. The artist plays with the discourse through the painting’s 2-D and 3-D relationship as well as the confusing points of perspective that lead the viewer from one picture plane to another. The arch acts as an entrance to the painting. In all its magnificence and beauty the arch is a mythical element, in a state of unfinished perfection. Here the artist’s investment in, and homage, to Ethiopian tradition becomes clear. For the arch is a visual representation of an image in one of the three Garima Gospel books, in particular, Garima III.81 These works, from the monastery of Garima, not far from Adwa in northern Ethiopia, are the oldest manuscripts in Ethiopia. Recent carbon dating shows that two of them appear to date from the sixth or seventh centuries CE. Indeed Garima III, radiocarbon dated to 330-650 CE, is the oldest surviving illuminated Gospel book in the world.82 The source image for the arch here was painted to form a frame for the canon tables invented by St Eusebius (ca. 260 – ca. 340 CE) to highlight similar passages in the four Gospels. As Francis Watson has noted, ‘The primary function of these tables is to make parallel passages available for consultation, but they also serve to display the harmonious order underlying the apparent chaos of gospel interrelations’.83 So just as the Garima arch functioned to assist believers to gain access the Gospels, the artist’s arch serves here to provide an entrée to the topography of Jerusalem and its future destiny. In particular, the arch evokes an ecclesiastical tradition that runs from events in Galilee and Judea, especially in Jerusalem, with its Temple, where Christ was crucified and, for his believers, rose again in the first century CE, to Ethiopia, in the fourth to sixth centuries CE, when Christianity arrived and became embedded. So, with this premise, the painting as a plan has the sense of vision and archaeology all at the same time. The archway is a feature of the Temple of Israel, with all its beauty, but it also resembles a ruin or a relic of what has past. The arch enables the juxtaposition of the new and the old within the same metaphor.

The mythical creatures in the painting are the Watchers of 1 Enoch 1-36. They are not properly of this world and are positioned across the canvas to describe the sense of someone, like Enoch himself, now entering into paradise and heaven. A characteristic feature of the Garima canon tables is their decoration with colorful birds, some of them unique to Ethiopia, and these have prompted the inclusion of birds within the compositional scheme. But the artist has anonymised the birds, so that they are unrecognisable compared with any bird on earth and look like hybrids, not to denigrate them (as if they were like the detestable birds of Lev 11:13-19!) but to proclaim that these are, in fact, glorious avian creatures of heaven.

Also directly connecting with Ethiopia are the eyes on the surface of the painting. They are good Ethiopian eyes looking directly at the audiences almost as vetting agents, very much like the apotropaic eyes on Ethiopian prayer scrolls. They are observing the viewer’s every move and watching the proceedings going forward, from the mythical realized past and beyond. Ethiopian tradition is acting here as the gateway to Heaven. Here exists the Temple of Israel in Ethiopian ecclesiastical guise and this exists as the portal linking the painting straight back to the original text of 1 Enoch. Theologically speaking, a path to salvation is through 1 Enoch.

On to the next painting?

Enoch’s Journeying to the Ends of the Earth

__

74 The discussion of this painting is gratefully reproduced by permission of the Biblical Theology Bulletin, Volume 50:3 (August 2020), 136-153, in an article entitled ‘Painting 1 Enoch: Biblical Interpretation, Theology, and Artistic Practice’, by Philip Esler and Angus Pryor.

75 See Kelley Coblentz Bautch, A Study of the Geography of 1 Enoch 17-19: No One Has Seen What I Have Seen (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

76 Milik, The Books of Enoch, 36-37; VanderKam, Enoch, 137; Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 318.

77 Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1959), 44-45.

78 James C. VanderKam, Enoch: A Man for All Seasons. Studies on Personalities of the Old Testament (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press ,1995), 57. Also see Jub 8:12, 19 and Charles, ‘1 Enoch’, 54.

79 Richard Bauckham, ‘James and The Jerusalem Church’, in The Book of Act in Its Palestinian Setting. Volume 4, (ed.) Richard Bauckham (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1995), 415-480.

80 Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 315.

81 Judith S. McKenzie, and Francis Watson, The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia. Manar Al-Athar Monograph 3. (Oxford: Manar Al-Athar, 2016), 33.

82 Ibid., 1.

83 Ibid., 147.