The Descent of the Watchers

(1 Enoch 6:1-7:1)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

1 Enoch 6:1-7:1 represents one of the great moments in human myth-making. It is a myth that is foundational for the Enochic tradition and continuously alluded to throughout the text. That is why it is placed at the beginning of the drama of 1 Enoch. 27 The passage begins as follows:

When the sons of human beings had multiplied, in those days, beautiful and comely daughters were born to them. And the Watchers, the sons of heaven, saw them and desired them. And they said to one another, ‘Come, let us choose for ourselves wives from the daughters of human beings, and let us beget children for ourselves’ (1 Enoch 6:1).28

The myth itself was not invented by the Enochic authors, for they drew their primary inspiration from Gen. 6:1-2 in formulating it:

When human beings began to multiply on the face of the ground, and daughters were born to them, the sons of God saw that the human daughters were fair; and they took to wife such of them as they chose.

Nevertheless, the Enochic scribes subjected the basic story to three major modifications.

The first change consisted of the alteration of the short third person narrative in Genesis to a detailed drama. Even in 1 Enoch 6:1-2 we have the introduction of the Watchers speaking to one another, to urge their taking of human wives and propagation of children. In 1 Enoch 6:3-7 this dimension is greatly amplified with the introduction of a chief amongst them, Shemihazah, who, to prevent backsliding, urges them to take an oath that they will all do this deed and thus commit a great sin, a suggestion in which they acquiesce (vv.3-5). The action is then given a dramatic setting with their descent to earth in the region of Mount Hermon (v. 6) in the days of Jared (the patriarch who was Enoch’s father; Gen. 5:15-18). We are also provided with a dramatis personae, in the form of a list of their leaders (v. 7). At the same time, as the drama later develops it does not merely concern the Watchers who defected (not ‘fell’) from heaven, but also God, the rest of his angelic courtiers in the heavenly court, and Enoch himself, 29 all of whom engage in significant dialogue and act out particular roles.

The second change was in the additional element that the Watchers taught the women special knowledge. Thus, we come to the climax of the Watchers’ action in 1 Enoch 7:1, when the die is well and truly cast:

These and all the others with them took for themselves wives from among them such as they chose. And they began to go in to them, and to defile themselves through them, and to teach them sorcery and charms, and to reveal to them the cutting of roots and plants.

Thirdly, the Enochic scribes pushed other features of the Genesis source in a much darker direction, so that the secession of the Watchers from heaven acquired a central role in the evils besetting humanity and the earth. The Genesis account continues as follows:

The Nephilim were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of human beings, and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men that were of old, the men of renown. The Lord saw that the wickedness of humanity was great on the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of their heart was only evil continually (6:4-5).

The text suggests that the union of the sons of heaven and human daughters produced Nephilim, literally ‘Fallen Ones’ but later, in Num 13;33, identified as giants. Yet these are presented in a totally positive way, as renowned mighty men of old. While the next verse attributes evil to humanity, there is no sign that the Nephilim were responsible. Not so in the interpretation of the Enochic scribes, although the relevant passage has textual uncertainties:

And they (sc. the Watchers) conceived from them and bore to them great giants. And the giants bore Nephilim, and to the Nephilim were born (Elioud?). And they were growing in accordance with their greatness. They were devouring the labor of all of the sons of human beings, and human beings were not able to supply them. And the giants began to kill human beings and to devour them (1 Enoch 7:2-4).

The Giants are no longer depicted in a positive light. Rather, their birth plays a direct role in the propagation of evil on the earth and a causal connection is established not evident in the Genesis account. As the drama develops, moreover, we will observe that further negative consequences for humanity and the earth will persist until the End-Time.

Other details of the Genesis account are also modified. The ‘sons of God’ in Gen 6:2, whose nature was the cause of much controversy among Jewish and Christian writers later,30 are now unambiguously construed as heavenly beings, the Watchers, angels with a duty to guard the heavenly court, at the centre of which was the divine sovereign. The word ‘watchers’ was originally functional, referring to the role of angels in heaven ‘to watch’ what was occurring in heaven and on earth, so as to alert God to problems that were arising.31 Not all ‘watchers’ seceded from heaven. To designate those angels who did descend and marry human women, it is helpful to employ ‘Watchers’, with a capital letter.

Later in the text the authors attribute to God a long speech in which he sets out his reasons for wanting to punish the Watchers for leaving heaven to marry human wives (1 Enoch 15:3-7). God construes their action as a form of rebellion, and here the prevailing metaphor is that of courtiers in Ancient Near Eastern or Hellenistic courts who turned against their monarch. In this case, however, it is rebellion in the sense of an abandonment of a set of rules that God has established for the good order of his cosmos. The Watchers were made immortal and had no need of women. They should have stayed in heaven: ‘The spirits of heaven, in heaven is their dwelling’ (1 Enoch 15:7). Instead, they descended to earth. The primary issue is that ‘immortal spiritual beings not needing to engage in reproduction have joined themselves with mortal physical beings, beings of flesh and blood, who do need to reproduce.’ 32 This means that the Watchers have defiled themselves in the sense explained by anthropologist Mary Douglas, in that they have breached boundaries that are meant to keep separate realms apart.33

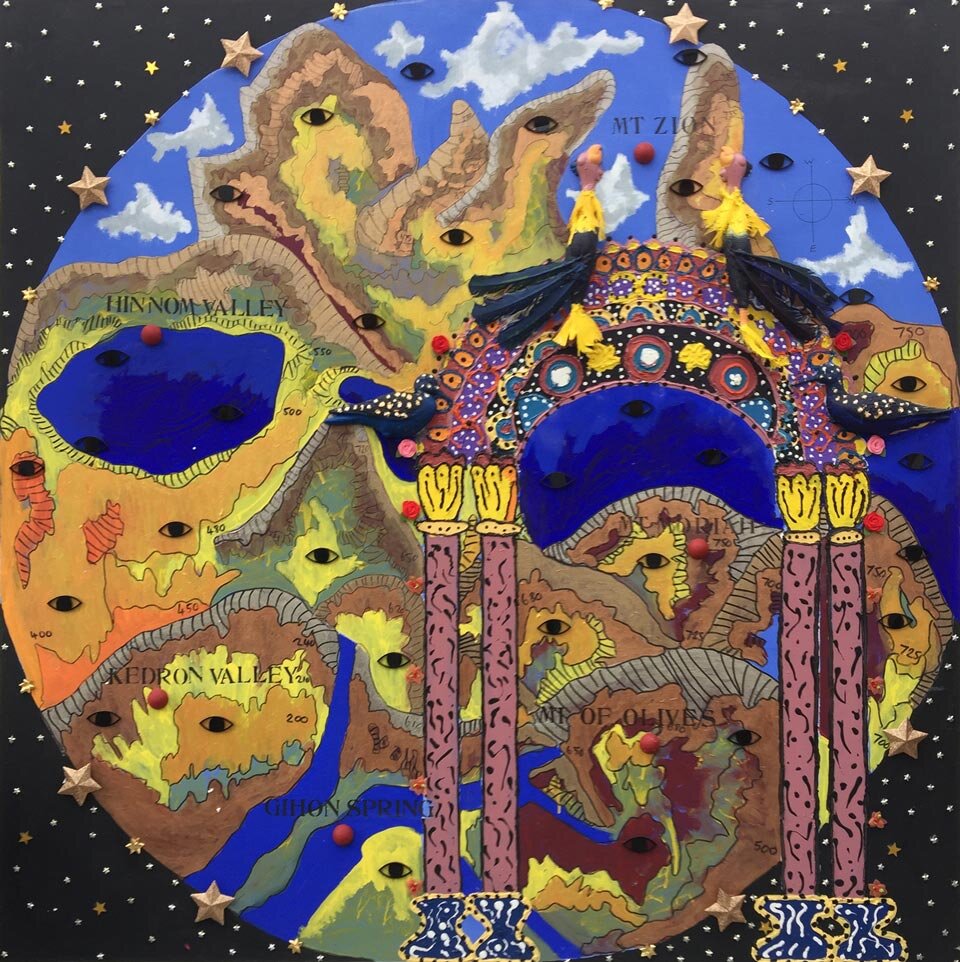

The artist’s starting-point for the painting The Descent of the Watchers (1 Enoch 6:1-7:1) is the memorable account of this event in 1 Enoch 6:1-7:1. His focus is specifically upon the Watchers’ descent to the women. In this painting he does not concern himself with the fact that the Watchers taught them magic and sorcery, or with the grievous consequences of this action for humanity and the earth. Those matters will be the subject of the next two paintings. In The artist has found inspiration in the work of British artists John Flaxman (1755-1826) and William Blake (1757-1827), both of whom (in 1821 and 1822 respectively) drew small and intimate studies of the Watchers descending to women on earth.

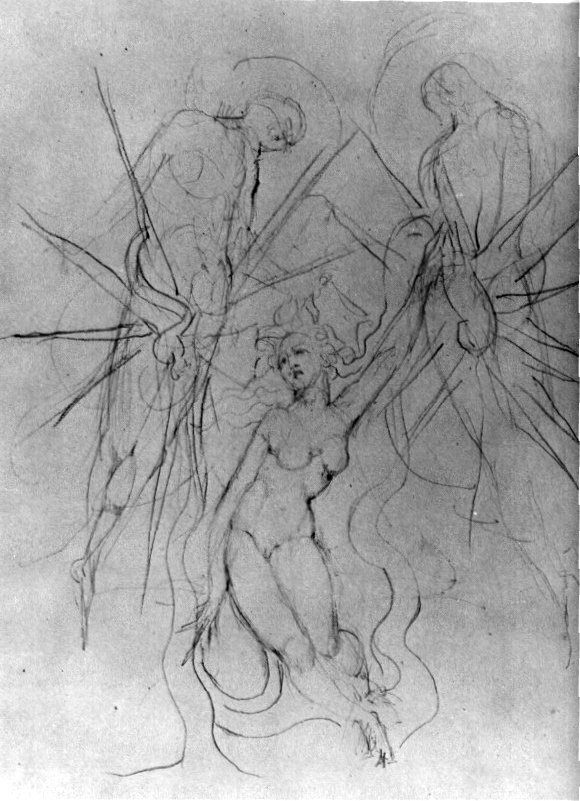

Flaxman and Blake were inspired to create these images by the publication of the first modern translation of 1 Enoch by Richard Laurence in 1821 based on the 1 Enoch manuscript supplied to the Bodleian Library in Oxford by the Scottish adventurer James Bruce.34 Flaxman’s drawing, Angels Descending to the Daughters of Men (Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery of Art, USA) is a composition depicting a group of Watchers literally falling downwards towards the great beauty of the human women. In Blake’s drawing from 1822, Two Angels Descending to a Daughter of Man (Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery of Art, USA) (see image below),35 the daughter is in evident distress as the two Watchers hover above her in a threatening manner. Blake has used an over-drawing technique to make erotic suggestions through very simple marks. Both drawings depict the Angels as faceless, threatening entities, while Blake’s drawing shows the woman in a compromised position, vulnerable and exposed.

In the painting, the artist has depicted one woman and one descending Watcher standing in direct confrontation with each other. The images are juxtaposed, with the woman depicted as standing vertically while the Watcher descends head-first as if in a precipitous dive. The Daughter in this instance takes the form of a comely woman with hair painted gold to symbolise perfection, who stands on a bed of white hydrangea blossoms to convey her innocence. The Watcher is falling in such a manner that he is targeting her, with his hand in direct contact with her body, suggesting what is about to happen. On one side, gold stars surround the Daughter, girding her in an attempt at protection. The Watcher is surrounded by red stars to suggest his fall from grace and the transgression of flesh that is about to take place. The lines, drawn both straight and curving, are also in red as they suggest the phallus and the imminent loss of innocence of the human Daughter. The red lines thus foresee what will happen in the next instant—like a still frame of the future. Highly coloured birds surround the Daughter’s head, a feature that again enacts and suggests the need for protection, while at the base of the Watcher’s head two blackbirds foretell his fate.

The background composition is painted in parallel lines, all horizontal, to suggest the heavens meeting the earth. The golden sun and its rays penetrate a black sky to show where the Watcher has fallen from and, via the use of strata on the painting, how far he has fallen from his original starting point. On the Watcher’s side the red stars fall in unison, depicting the sin that is about to be committed. The composition in this part of the painting is also peppered with red jewels that look beautiful but come at a price. These boils of molten glass predict the future of the Watchers, encased in the earth’s molten core for long eons awaiting judgment. The single focus of the painting is this transgression: it deals with the fundamental violation of the boundaries that God established between the heavenly and the human realms. This produces lust and a loss of innocence and the ensuing corruption of humanity. There are consequences to these transgressions that can be seen in the sequence of the paintings.

Once again the artist has used real people to imprint onto the canvas (that is, by the pressing of flesh into paint) in order to give the work a real sense of the human and the sensual. The relationship between the painted and pressed markings convey the real rather than the observed. The objects that sit on the surface create multi-layers, giving not only the painting but also the text a three dimensionality. The post-conceptual nature of the painting, along with the objects on the canvas, creates a sense of textual space, both real and imagined. This painting—conveying as it does warning rather than celebration—acts out the text visually so that the viewer can read the narrative within it.

On to the next painting?

Asael Teaching Metalwork

__

27 George W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 165.

28 Translation Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch, slightly modified.

29 For a discussion of the presence of Enoch in heaven in 1 Enoch as modeled on a sage in an ancient Near Eastern royal court, see Philip F. Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watcher, 63-65.

30 Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 176.

31 Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 59.

32 Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 99.

33 Esler, ibid., 99-100.

34 Munro D. Paley, The Traveller in the Evening: The Last Works of William Blake (Oxford: OUP, 2003), 266-269.

35 A photograph of this drawing is available on Wikimedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blake_Two_Angels_Descending_Pencil_drawing_c_1822.jpeg