God and the End-Time Punishment

(1 Enoch 1:4-9)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

In the Book of the Watchers (1 Enoch 1-36) the narrative proper begins with the rebellion of the Watchers in Chapter 6. The five chapters prior to this constitute an introduction both to the Book of the Watchers but also to the whole collection (1 Enoch 1-108). These chapters begin with an introductory announcement:

‘The words of the blessing with which Enoch blessed the righteous chosen who will be present on the day of tribulation, to remove all the enemies; and the righteous will be saved (1:1).’25

Thereafter follows a first person discourse by Enoch, which begins with his credentials: he is a righteous man whose eyes were opened by God, who showed him a vision of heaven and earth, and he heard everything from the Watchers and holy ones and understood what they said. He now speaks about the chosen to a distant generation.

From verse 1 we realise that he is about to describe the terrible events of the End-Time, specifically of the day of tribulation (yom tsarah in Hebrew), culminating in judgment that results in the removal of sinners but also salvation for the righteous.

This judgment will constitute God’s definitive response to the problem of evil that has beset humanity—on the Enochic view, not from the actions of Adam and Eve but from Cain’s murder of Abel.26 This evil increased up until the time of Noah, with help from the Watchers who came to earth, was partially dealt with by God through the Flood and the punishment he then meted out to the Watchers and the Giants, but will persist until the End.

After this material follows the passage that forms the subject of the first painting in the exhibition, namely the appearance of God with his heavenly army at the End-Time. This theophany is depicted in exalted language.

Firstly, creation is convulsed:

All the ends of the earth will be shaken,

and trembling and great fear will seize them (the Watchers)

unto the ends of the earth.

The high mountains will be shaken and fall and break apart,

and the high hills will be made low and melt like wax before the fire.

The earth will be wholly rent asunder,

and everything on earth will perish (1:5-7).

Then there will be judgment for all:

With the righteous he will make peace,

and over the chosen there will be protection,

and upon them will be mercy (1:8).

But there is bad news for the wicked:

Look, he comes with the myriads of his holy ones,

to execute judgment on all,

and to destroy all the wicked,

and to convict all humanity

for all the wicked deeds that they have done,

and the proud and hard words that wicked sinners spoke against him (1:9).

The effect of 1 Enoch 1:4-9 is that the Enochic scribe has prefaced the whole collection with an opening statement about how the cosmic tale of sin and salvation will end—with God’s definitive acts in defeating evil and rewarding the righteous.

This would have provided reassurance to the audience of the work that no matter how bad things might get, especially for Israel, this was a story that would eventually have a happy ending. While God might delay in dealing with evil, in due course deal with it he would. 1 Enoch 1:9 is a powerful expression of that view.

Indeed, a case can be made for this being the most significant verse in the whole work. Certainly there is evidence that this was how it was regarded in parts of earliest Christianity. In the New Testament the Letter of Jude, after having mentioned the rebellion of the Watchers and their resulting punishment in v. 6, goes on in vv. 14-15 to quote 1 Enoch 1:9 verbatim as crucial to its argument. Thus a canonical New Testament text cites and hence sacralises the central theological affirmation of 1 Enoch, an ancient Jewish work that never found its way into the Hebrew Bible, or even, surprisingly in view of Jude 6 and 14-15, into the Apocrypha of the Christian Bible. Alone among all the Christian churches of the world, it was Ethiopian Orthodoxy that aligned itself with the Letter of Jude in recognising the theological significance of 1 Enoch 1:4-9, v. 9 in particular, and 1 Enoch as whole. The painting that is now described, God and the End-time Punishment (1 Enoch 1:4-9), has been created in a process of artistic making in dialogue both with 1 Enoch and with the Ethiopian tradition that alone honoured it.

It may seem illogical that this is the first painting in the sequence. Although it is a common device in both literature and film to reveal at the start what will happen at the end, so that the audience can anticipate what is coming, this does not usually happen in painting. This is not intended to nullify the narrative as a fait accompli but to act as guide or a warning that all the subsequent paintings in the series lead back to this event. As noted above, it reminds the reader of 1 Enoch and the viewer of these paintings that for the righteous and the cosmos 1 Enoch is a text with a happy ending. Ultimately, God will deal with the evil that subjugates humanity and creation itself.

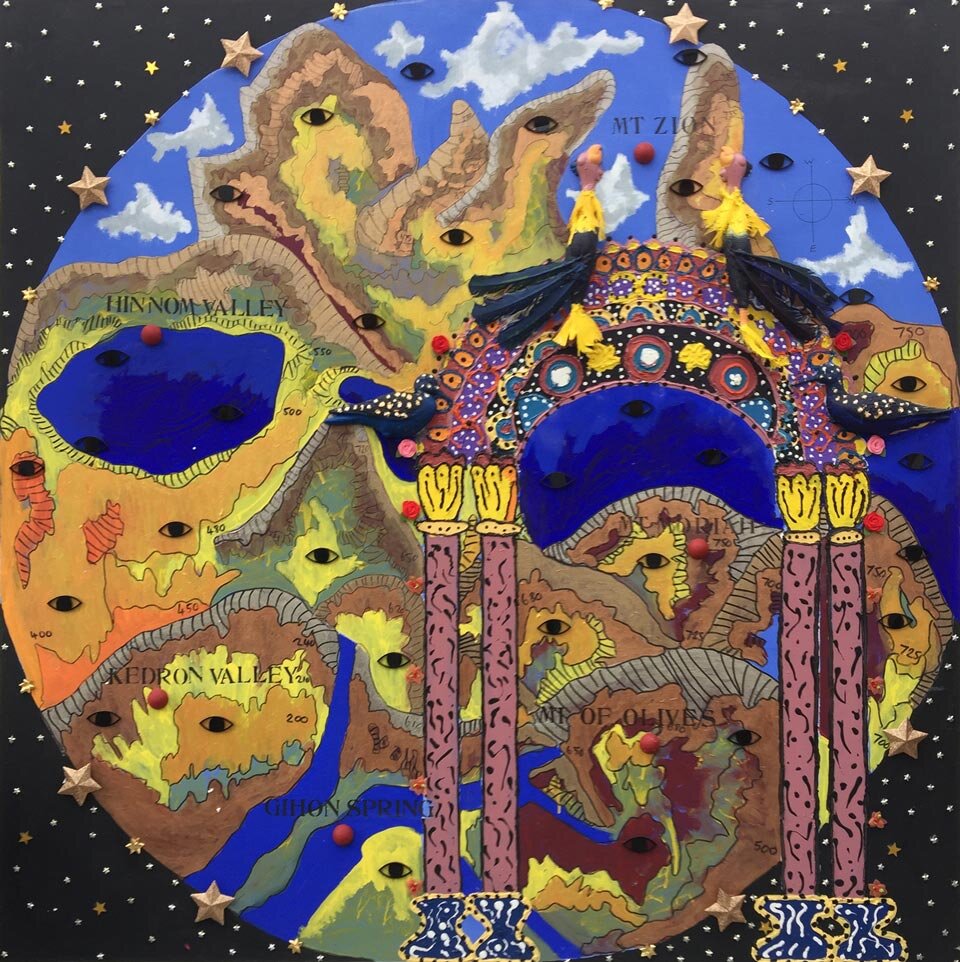

Compositionally, the painting is very simple, with its fundamental differentiation of the earth and the sky. The complexity of the painting lies in the fact that, as in any Last Judgment scenario, chaos ensues. In the top half of the painting we see God descending on two clouds from the Kingdom of Heaven. (The idea for this merges 1 Enoch 1:9 with the words ‘thy kingdom come’ in the Lord’s Prayer and was suggested to the artist by Esler). God is leaving the fortifications of his castle in the sky and bringing with him an army of myriads of warrior angels. He himself is not armed but is white and as pure as snow. Above each of his shoulders he has an archangel. One of them is Michael, acting as the general leading the attack. The angels go down in significance to the tiniest dots, a fearful sight for anybody to witness.

The sky itself is golden as on a lovely summer night when everything seems perfect—but the sins of the earth cannot be hidden.

The Ethiopian bowls serve as reminders of what we have lost: great beauty, wisdom and serenity. The black bowls have horns as the seventh seal is opened and we can almost hear the call to arms; the seventh seal is from Revelation 8 and is introduced here as a gesture to the role of 1 Enoch in Ethiopian tradition in linking Old and New Testaments. All the angels are dressed in Ethiopian clothing, which is to honour Ethiopia, which alone preserved the complete text of 1 Enoch.

The bottom half of the painting shows that all of humanity has been judged. The unrighteous have been covered in a black substance that boiled them alive. It appears as though their flesh has melted away like wax, just as the hills themselves will melt (1 Enoch 1.6). Human organs are left strewn about, brains and hearts all mixing together. Red paint seeps through the surface like congealed blood. Insects and animals are also covered, as if God is wiping the slate clean and preparing the surface to start again. Two wretches call through the mire as if for mercy, but it is all too late.

Two red antlers spring from the canvas like hands reaching out to the audience to warn them not to make the same mistakes as our forefathers. These antlers represent the ancient Nagar, a mysterious creature mentioned in 1 Enoch 90:38 and conceived of by the artist as lending their support to the narration of these texts, and who, as we will see, are ever-present in these paintings. The antlers also act as a reminder of the presence of Enoch, heaven’s messenger, who is telling the story and bringing it to our attention.

On to the next painting?

The Descent of the Watchers

__

25 Translation from George W. E. Nickelsburg and James C. Vanderkam, 1 Enoch: The Hermeneia Translation (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012), 19. Unless stated otherwise, all translations in this Catalogue will be taken from this work (and without specifying page numbers).

26 On evil in 1 Enoch, see Philip F. Esler, ‘Deus Victor: The Nature and Defeat of Evil in the Book of the Watchers (1 Enoch 1-36)’, in Philip F. Esler, ed., The Blessing of Enoch, 166-190; on evil originating with Cain’s murder of Abel, and not from Adam and Eve, see 172-173.